What was your role with THING, how did it inform the magazine’s direction and reception?

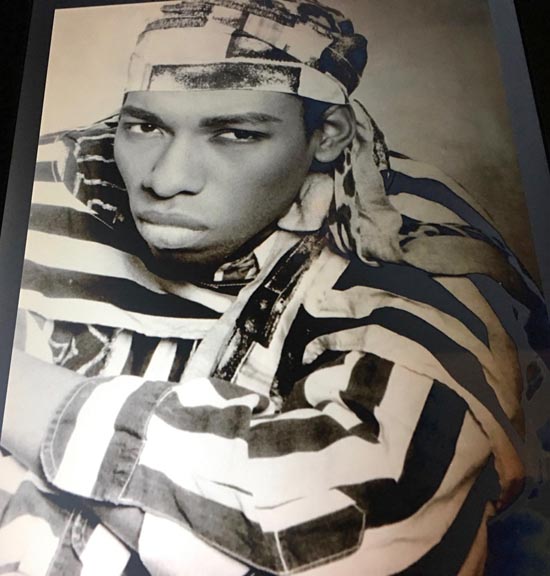

I appeared on Think Ink and THING magazine covers, and my role was purely I&G: inspiration and guidance. I was a hairdresser and worked for Bumble and Bumble, NYC; Vidal Sassoon, Chicago; and Louis Licari, NYC, a world-renown hair colorist.

I was a constant source of inspiration and trendsetting to Robert Ford, Trenton Adkins, and Lawrence (Larry) Warren because that’s the space we thrived and lived in as young Black creatives. We fed off of each other’s energy.

We thrived on discussing and dissecting Black cultural trends, consumption of European, American, and Asian fashion magazines, Black underground gay clubs that played exclusive House music, politics, and the AIDS crisis, unfortunately. It was a vigorous exchange, especially with Larry; he loved details, details, details, and so did Trenton. Trenton knew more about Vogue’s editor Diana Vreeland than she knew about herself, lol.

I was considered a neologist, notorious for coming up with catchy new words or phrases that would spread like wildfire. We put a spin on everyday life, and the Black gay community is well-known for this attribute but not adequately given credit at the same time.

Some of the phrases we coined are used today. Many have made their way into MSM, reality TV, and social media; it all started in the Black gay underground on the Westside and Southside of Chicago. That’s how Trenton’s “The Tee Glossary” column in Thing magazine was born. Can you live?

Why and how did THING serve as a platform for marginalized voices and non-traditional storytelling?

First and foremost, we did not view ourselves as marginalized people. To be marginalized means to be made ineffective or forced to watch without being able to help or change something. That was not us!

We did what we wanted to do. Went where we wanted to go. Saw who we wanted to see. And said what needed to be said. We contributed immensely to Chicago’s urban history and later influenced the world. Today that’s considered an Influencer. And influence we did!

Needless to say, Robert, Larry, and Trenton were champions and bulwarks of protecting Black underground culture: period. Being the geniuses they were, they knew that if we didn’t document and told our own life stories, somebody else would. Thereby increasing the stakes of minimizing our contributions to society, or worse, wiping us out altogether.

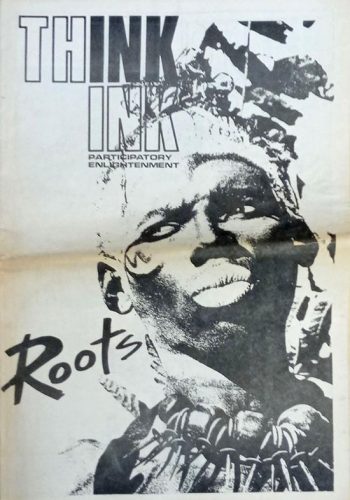

But way before THING magazine, there was Think Ink magazine. Think Ink was targeted at Black middle-class young adults but became too expensive for Robert to self-publish due to its large format. Two issues were published: November 1987 and spring 1988 — so the crew came up with another idea two years later. That’s when THING was birthed to tell our stories.

And storytelling is part of our roots! Black people are always telling each other stories; that’s just what we do. However, the ’80s presented the computer, which allowed THING to be self-published, bypassing traditional publishing techniques, which were complicated, time-consuming, and expensive. Otherwise, oral stories are vulnerable to the perils of time; people move on, details are lost, and buildings are demolished. And suddenly, there’s no more history — especially Black gay Chicago history.

Publishing Think Ink and THING magazines changed that trajectory. Future generations of artists and their followers can see what happened in Chicago straight from the horse’s mouth.

Can you live?

How do you feel magazines have a role now in challenging the status quo, and do you think that will remain?

Right now, there’s a resurgence in print. And with print comes journalistic standards that offer a long-term strategy and a haven for those who prefer security for their work.

However, with the ease of digital publishing, anyone can say anything, true or false, and gain notoriety at the push of a button. And that’s a seductive reality. I call it “keyboard contagion” because lives can be changed instantly, for better or worse.

Because today’s artists have many options for publishing their work, I say choose wisely, but remember that print lasts forever. Hack a server or take a satellite offline, and no one will know you’re an artist if all your digital-based media is erased. It’s here today and can be gone tomorrow. Print offers a balance to this inherent risk. The Subscribe exhibition at the Art Institute proves this point.

This is all happening in cycles, so how long this renewed interest last remains to be seen.

Anything else?

Chicago during the ’80s was a magical place for the cultural influences that were sweeping the city. There was a real sense of brotherhood and pride in the Black and Latino underground gay communities. A coalition of sorts, long before the word “pride” was co-opted by mainstream media.

This is how Chicago elected its first Black mayor Harold Washingon. Under Washington’s leadership, the city started making bold moves toward equity and inclusiveness in minority contracting. For the first time in modern history, contracts for women and minorities became front and center.

This was the political backdrop for Think Ink and THING magazines. We were being our authentic selves, an eclectic group of young Black adults from Hyde Park and South Shore, and not trying to fit into anyone else’s reality. And to give credit, I recently learned from photographer and living legend Patric McCoy, that we stood on the shoulders of Black Chicago artists of the ’60s and ’70s.

Thanks to the computer, we were lucky to be among the first generation to self-publish our legacy in print. We created the world we wanted to live in.